The relationship between alcohol and mental health

Concerned about someones alcohol use? Don’t forget to talk about mental health too!

Alcohol is an ingrained part of British culture we use it to celebrate weddings and grieve death, toast the new year and de-stress from a busy week at work. Attitudes towards alcohol have changed throughout history; during the medieval period beer was a staple part of the British diet. During the Early modern period the Protestant and Catholic Church viewed alcohol as a gift of God that was created to be used in moderation for pleasure, enjoyment and health, drunkenness however was a sin. Victorian England saw the rise of the temperance movement from which the term teetotal emerged. In contemporary British culture alcohol use is a normalised and accepted part of life.

The media and popular culture promote many misconceptions about alcohol use in the general public. The working class are often demonised in relation to alcohol use, however people with possible alcohol dependence are actually more likely to be of a higher social class and well educated (Alcohol Concern 2015). Similarly, young people are often the focus of negative reporting about their high levels of alcohol use, recent data however suggests they are increasingly turning away from alcohol. There has been an 11% decrease in the number of young Brits binge-drinking once a week (from 29% to 18%) and the number of teetotallers in this age group has also risen to more than a quarter (27%) of the total (ONS 2013).

Obviously our historical and cultural relationship with alcohol is more complex and diverse than this brief explanation, but it is clear that our perceptions and attitudes towards alcohol are fluid rather than fixed.

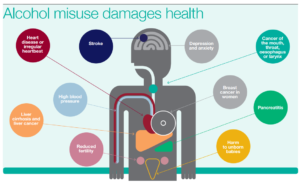

Whilst the majority of alcohol use isn’t problematic, for many people alcohol can and does have negative consequences. Support for problematic alcohol use often focuses solely on addiction despite the majority of people also experiencing mental health problems, most commonly depression and anxiety (Drugscope 2015). In fact, this is the norm rather than the exception, research conducted by Weaver et al (2002) identified that 85.5% of users of alcohol services experience mental health problems, a consistent finding across alcohol services nationally. Alcohol is also significantly linked to increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Over half of the mental health patients who died by suicide during 2014 had a history of alcohol or drug misuse, only a small group of whom were accessing a specialist substance misuse service (The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness 2016).

The relationship between mental health and alcohol use is complex and there is no definitive causal link. However, whether problematic alcohol use or mental ill health came first, having one condition makes it significantly more likely the other will develop.

The term ‘dual diagnosis’ is used to describe people who have both mental health and substance use problems. However, it is not an official psychiatric diagnosis and many people with problematic alcohol use don’t receive a mental health diagnosis. Alcohol use is often a barrier which prevents people from being able to access mental health services, this seems perverse when there is such a strong relationship between them.

Alcohol dependence is identified in the both ICD 10 and DSM V, the diagnostic manuals used to classify mental health disorders. Despite being a psychiatric diagnosis services for substance use have historically been commissioned and delivered separately from other mental health services in the UK. Services have been designed to manage single ‘primary’ problems as opposed to multiple needs (Revolving Doors & MEAM 2011). Consequently, people with dual diagnosis often experience a ‘ping pong’ effect with services not willing to take responsibility or able to meet their multiple needs and have therefore fallen between the gaps of service delivery.

Since the publication of The Dual Diagnosis Good Practice Guide (DoH, 2002) there has been an absence of further policy to build on the foundations it created. Dual diagnosis has therefore fallen off the agenda of many commissioners and policy maker’s despite being regular identified as a key area of need for people accessing services. This situation has been further exacerbated by the radical structural reorganisation and re-commissioning of health and social care services over the past few years. Currently dual diagnosis support is based on postcode lottery, often relying on enthusiastic and dedicated practitioners.

The complexity of the relationship between mental health and alcohol needs to be acknowledged to enable an effective response to both conditions. To support recovery, it is essential to meet the holistic needs of a person which means addressing both problems together. Therefore, if you’re concerned about someone’s alcohol use don’t forget to talk about their mental health too.

Rich Bell, Mental Health Trainer. Community Links

For more information and advice about alcohol use visit www.drinkaware.co.uk or www.alcoholconcern.org.uk

Reference list –

Alcohol Concern (2015) The way we drink now. Alcohol Concern & Drinkwise

Department of Health (DoH) (2002), Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide: Dual Diagnosis Good Practice Guide, HMSO, London.

Drugscope (2015) Mental health and substance misuse. http://www.drugwise.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/CoexisitingMHandSMfull.pdf

Office of National statistics (2015) Adult Drinking Habits in Great Britain, 2013. http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/compendium/opinionsandlifestylesurvey/2015-03-19/adultdrinkinghabitsingreatbritain2013

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. Making Mental Health Care Safer: Annual Report and 20-year Review. October 2016. University of Manchester. http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/cmhs/research/centreforsuicideprevention/nci/reports/2016-report.pdf

Revolving Doors & MEAM (2011), “Turning the tide: a vision paper for multiple needs and exclusion”. www.meam.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/turning-the-tide.pdf

Weaver, T., Charles, V., Madden, P. and Renton, A. (2002), Co-Morbidity of Substance Misuse and Mental Illness Collaborative Study (COSMIC), Department of Health, London.